India launched Bharat Taxi Service as First Cooperative-Owned Digital Mobility Platform

India launched Bharat Taxi Service as First Cooperative-Owned Digital Mobility Platform India places World’s First Live Commercial Order for Hyperloop-Based Cargo Logistics

India places World’s First Live Commercial Order for Hyperloop-Based Cargo Logistics How Weigh-in-Motion Systems Are Revolutionizing Freight Safety

How Weigh-in-Motion Systems Are Revolutionizing Freight Safety Women Powering India’s Electric Mobility Revolution

Women Powering India’s Electric Mobility Revolution Rail Chamber Launched to Strengthen India’s Global Railway Leadership

Rail Chamber Launched to Strengthen India’s Global Railway Leadership Wage and Hour Enforcement Under the Massachusetts Wage Act and Connecticut Labor Standards

Wage and Hour Enforcement Under the Massachusetts Wage Act and Connecticut Labor Standards MRT‑7: Manila’s Northern Metro Lifeline on the Horizon

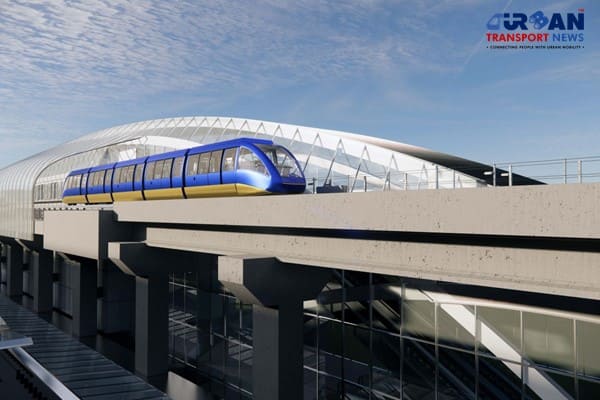

MRT‑7: Manila’s Northern Metro Lifeline on the Horizon Delhi unveils ambitious Urban Mobility Vision: Luxury Metro Coaches, New Tunnels and Pod Taxi

Delhi unveils ambitious Urban Mobility Vision: Luxury Metro Coaches, New Tunnels and Pod Taxi Qatar approves Saudi Rail Link Agreement, Accelerating Gulf Railway Vision 2030

Qatar approves Saudi Rail Link Agreement, Accelerating Gulf Railway Vision 2030 UP Govt plans to introduce Water Metro services in Ayodhya, Varanasi & Prayagraj

UP Govt plans to introduce Water Metro services in Ayodhya, Varanasi & Prayagraj

IWD 2022: Birth of an Era for Empowered Women in Transport sector

Women constitute almost 50% of the total population in India. They are the key agents to achieve economic, environmental or social growth of the country. Despite this, women are discriminated and considered weak as compared to their male counterparts, especially in the rural and semi-urban areas. Even if she desires to break the glass ceiling and improve her social status, limited access to credit, education and healthcare surface as a hindrance. Although the need for women empowerment by providing equal rights to participate in society, education, skill development and employment can’t be denied any longer.

Even in the current era Public Transport is a male-dominated sector that contains gender gaps throughout all levels of the workforce. Gender gap can be defined as the unequal outcomes experienced between women and men in the workforce, and women’s restricted access to rights and assets. More broadly, male dominated sectors consist of industries and occupations where women comprise less than 25% of job incumbent’s .They reflect a more traditional workplace, one created, maintained and controlled by males since inception. Progress in closing most gender gaps is slow. The gender gaps with respect to key labour market indicators have not narrowed substantially for the past 20 years. Differences remain in employment rate, part-time work, unpaid care and family responsibilities, professions and decision-making positions, working conditions, wages, and the possibilities for economic independence between women and men.

United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

GOAL NO.5 (Gender Equality): Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls

Target 5.5: Ensure women’s full and effective participation and equal opportunities for leadership at all levels of decision-making in political, economic and public life.

Indicators 5.5.1: Proportion of seats held by women in (a) national parliaments and (b) local governments.

Indicators 5.5.2: Proportion of women in managerial positions

Global & Indian Statistics in Female representation in Transport Industry

In the European Union, only 22% of the labour forces in transport services are women, compared to 46% in the general economy. In Air Transport the share of women is 40%, almost double the average for all transport services. This large female presence in the air sector is due to flight attendants and various ground services dominated by women, such as check-in and customer services. But at the same time, some employee groups, such as pilots, are heavily dominated by men. The situation in other transport sectors is much worse: indeed, the percentage of women is 20% in water transport and only 14% in land transport. The situation doesn’t improve in the urban public transport sector, with an average 17.5% of female employees.

The share of women’s participation in the transport sector also differs by mode. For example, the employment rates in the railway industry in the United Kingdom are 16% female and 84% male, even though 47% of its national workforce is female (Women in Rail, 2015). In the European Union’s urban public transport sector, women account for approximately 18% of total employees on average, ranging between 5% to 31%, but represent less than 10% of drivers (WISE, 2012).

According to the policy, the rural and urban female labour force participation rate (FLFPR) in Tamil Nadu is 35.1% and 23.6%, which is higher than the national average by 15.4% and 7.5%, respectively. Female participation in various Central government jobs is as low as 10.93 per cent out of a total 30.87 lakh employees.

Barriers to the women in Public Transport Jobs

Regarding women’s recruitment and employment, various factors have been identified as barriers. The most important emerge from a survey carried out in railway companies and trade unions. It seems that the physical effort required in some jobs induces companies to be sceptical about employing women and discourages them from applying for a job position. On the one hand, gender-related stereotypes and prejudices are still largely common in European railway companies and the typical male work culture prevails. On the other, working in a railway company does not appear attractive to many women because of shift work and spatial mobility (e. g. for locomotive drivers, conductors/on-board personnel), which represent barriers for women with caring responsibilities. Finally, health and safety at work and hygiene issues (e. g. the lack of appropriate infrastructure for women, such as separate toilets or toilets at all, for instance, on board freight trains) represent other major barriers to female employment, even if they seem relatively easy to overcome.

The barriers which could account for the low number of women employed in the sector:

- “Contextual barriers” of work organisation in the sector, for example rolling shift work;

- “Barriers of inadvertence” related to shortages of equipment, for example the lack of facilities, and

- “Barriers of discrimination” based on stereotypes and a male working culture leading to a lack of recognition and support

Why are women under-represented?

The main causes of the under-representation of women in the transport workforce are the harsh working conditions, a stereotype masculine image of the transport sector, security problems (particularly in the night -time urban transport sector), recruitment and reconciling work and private life. “The gender related stereotypes still occur in various modes and in general there is a typical male work culture.

There are records of quite a number of experiences of women seafarers and their difficulties in pursuing a career at sea. Several women denounced being victims of sexism from staff at their training institutions and many women also reported problems with some male colleagues of sexual harassment.”

Why we need to add more participation of the women in Public Transport work force?

Gender diversity in the workplace does not only benefit women. Mounting evidence shows that it is a benefit to societies, economies, the environment and enterprises themselves. Greater gender equality or diversity in the transport workforce will not only address the discrimination women face in the workforce as a matter of human rights and fundamental principles and rights at work, it will also create more economic efficiency leading to poverty reduction. Poverty rates are higher for women than for men on a global level, in both urban and rural areas (World Bank, 2018). Existing gender inequalities also make women and girls more vulnerable than men and boys to poverty (World Bank, 2011). Increasing women’s participation in the workforce could thus play an important role in poverty reduction.

The five Priority Areas to improve women participation in Public Transport are given below:

- Increasing female labour market participation and equal economic independence;

- Reducing the gender pay, earnings and pension gaps and thus fighting poverty among women;

- Promoting equality between women and men in decision-making;

- Combating gender-based violence and protecting and supporting victims; and

- Promoting gender equality and women‘s rights across the world.

Despite the benefits of gender equality in the transport workforce, women who decide to pursue a career in the transport sector encounter severe challenges. Studies have shown that such challenges can be broadly categorised into seven groups,

- Work organisation (e.g. opportunity to do part-time work, or teleworking);

- Work-life balance (e.g. parental leave, childcare);

- Health and safety at the workplace;

- Working culture;

- Wages;

- Career, Qualification and Training

- Recruitment.

Attracting women to the sector can help companies to recruit new staff, improve work-life balance, and ensure better working conditions for both genders. Women bring additional skill sets to the industry, from communicative skills to their ability to diffuse potentially volatile situation; thus we see the emergence of a new and better quality of public transport. Many International Organisations related to Transport like UITP, ITF agreed that strengthening the women employment in transport sector is to benefit of the whole sector, the companies and their employees.

- More women means more talents integrated in the company , a broader view on innovation , more additional and complementary skills like people orientation or communication skills of women.

- More women working in typical made dominated sectors usually improves the working conditions for all; it contributes to a better work environment and sense of respect and thus an improvement of the attractiveness of the job.

- The demographic change creates problem for companies and they cannot afford to do without women.

- It is a matter of equal opportunities more women in Public Transport contribute to enhance the image of the Public Transport firms and the transport sector.

Even though, there is a lack of gender diversity in technical and operational divisions, and in management positions. The representation of women is high in administration and customer service. The public transport sector does not

currently provide women with adequate training opportunities and representation in unions. They are subject to poor working environments, safety and health concerns, lack of facilities, including decent sanitation facilities, as well as violence and harassment from colleagues and passengers.

To attract and retain women to the sector a bundle of activities in different areas are necessary, which are mentioned here with some concrete examples:-

Recruitment policy: Address and welcome specifically women directly into the company. Negotiation of a recruitment procedure between the trade unions and workers’ representatives.

Qualification and training: Recruit young women for professional education, assure equal access for women to vocational training and avoid a “glass ceiling effect”.

Work-life balance: Introduce working time models that allow a better reconciliation of work and social/family life which include instruments allowing for the integrating of individual‘s wishes and needs.

Health and safety at work: Adapt occupational health & safety, workplace ergonomics, workplace security, and provide appropriate facilities like toilets, canteens, lockers, break rooms and changing rooms.

Equality in wages: Analyse the “gender pay gap” and develop policies to eliminate it.

Working culture and gender stereotypes: Change the corporate cultures from a male working culture to a diversity culture, sensitise the management on gender stereotypes and unconscious bias and include management, trade unions and workers representatives in the activities.

STU’s policies: Set clear & measurable targets and develop instruments to implement them with a top-down approach.

Promoting employment by preventing violence against women transport workers

Decent Work in Transport for women: Transport jobs can be well paid, rewarding and offer long term career opportunities. Unfortunately, and unacceptably, few women are employed in these jobs and some positions fall below the standard of decent work. One of the barriers to a career in transport is workplace violence.

Why action is needed for the violence against women?

- Jobs in the transport sector are highly gendered and unequal, as is access to transport services. As a result, women’s voices are all too often neglected when it comes to transport planning and the pursuit of decent work.

- Transport is still regarded as ‘no place for women’ in many countries/sectors around the world. Women in the transport sector often find themselves stuck in low(er) paid/low(er) status jobs with few, if any, opportunities for career development.

- Violence against transport workers is one of the most important factors limiting the attraction of transport jobs for women and breaking the retention of those who are employed in the transport sector.

What constitutes violence at work?

Violence can be defined as a form of negative behaviour or action in the relations between two or more people. It is characterised by aggressiveness which is sometimes repeated and sometimes unexpected. It includes incidents where employees are abused, threatened, assaulted or subject to other offensive acts or behaviours in circumstances related to their work. Violence manifests itself both in the form of physical and psychological violence. It ranges from physical attacks to verbal insults, bullying, mobbing, and harassment, including sexual and racial harassment.

External violence – workplace violence committed by external intruders who have no legitimate relationship with the workplace and who have undertaken criminal acts such as vandalism, robbery, sabotage or terrorism;

Service-related violence – aggressive acts by customers or clients of a service or a business;

Internal violence – aggressive acts by current or former employees or other persons with an employment-based relationship with an organisation (this includes workplace bullying and harassment); and,

Organisational violence – involves organisations placing their workers in dangerous or violent situations or allowing a climate of bullying or harassment to thrive in the workplace.

As a consequence of jobs being defined as ‘men’s work’ and women being underrepresented in the very institutions that might initiate some change, poor working conditions prevail and women are continually disadvantage by out of date structures, workplace arrangements and attitudes. Examples of ‘traditionally male’ transport jobs are listed in Table 1, alongside various roles that have been ‘feminised’ and/or ‘opened’ to women.

| Transport Mode | Traditionally Male | 'Feminised’ or ‘opened’ to women |

| Urban Transport | Bus Drivers | Tram (and Bus) Drivers |

Technically speaking, harassment, bullying and violence are also ‘gender-intensified’ barriers to working in the transport sector – men are bullied, harassed and subject to violence at work as well as women – but in practical terms it needs to be addressed as a ‘gender-specific’ problem. Transport records one of the highest levels of violence towards employees and this issue proved to be the main concern raised by women during the research for this ILO study. While the devastating effects of violence towards women are evidenced across all transport sectors and countries throughout the world, the root causes and perpetrators (e.g. co-workers, customers, supervisors, and managers) will differ and therefore demand sector-specific and country-specific policies to address this problem.

Training to address workplace violence in the transport sector could include:

- Improving the ability to identify potentially violent situations;

- Improving the capacity of event appraisal, active coping and problem-solving;

- Instilling interpersonal and communication skills that could prevent and defuse a potentially violent situation;

- Enhancing positive attitudes towards creating a supportive environment;

- Assertiveness training, as required, according to risk assessment;

- Self-defence training, as required, according to risk assessment.

Involving Self Help Groups in Transport

Women in rural areas are now able to create independent sources of income. While there were many young semi-literate women who have home-grown skills, the absence

of capital and regressive social norms prevents them from taking a full plunge in any decision-making role and setting up their own independent business. The self-help group movement has been one of the most powerful incubators of female resilience and entrepreneurship in rural India. It is a powerful channel for altering the social construct of gender in villages. Women in rural areas are now able to create independent sources of income. If we are engaging the women as part time while in Peak hours in Ticket counters, Ticket Validators in Express/Mofussil Bus Services than appointing the conductors as full time, the establishment cost will be considerably reduced.

Recommendations & Conclusions

It is possible to identify a number of specific opportunities for action to promote women participation in transport as detailed below:

- Encouragement needs to be given to address equality issues in STU policy.

- Identify the challenges and barriers to women in the transport workforce, and ultimately improve the level of gender equality in the sector

- Encouragement needs to be given to the various transport sector skills dialogues and such initiatives as the Transport Planning Skills Initiatives, Customer Care centres, and Ticket Checking Inspection areas are to explore further the gender imbalance in their sectors.

- Working conditions in transport, most notably working time and working away from home, can push women out of the industry. Provision for Rule to woman in Flexible working patterns, extended hours, variable start/finish times, shift-work, and 24x7 operations (sometimes for 365 days a year) .

- Our Government should form the policies in STU’s ,are relevant to the education and training, hiring and retaining of women, as well as labour laws that can set a legal framework for gender equality. Specific examples, such as the female labour force participation rate, gender parity index for tertiary education enrolment, STEM academic disciplines’ female tertiary attainment rate, maternity leave and equal pay law.

- The government has taken several measures to increase representation of women in the government jobs, which inter-alia includes maternity leave for 180 days, child care leave for 730 days, child adoption leave for 180 days, special allowance for women with disabilities and exemption from payment of fee for examination conducted by Union/State Public Service Commission and Staff Selection Commission, etc.

- As the establishment cost is more when compared to other variable costs. It is hereby suggest to involve the women self-help groups in doing the ticket validating process in bus stops for Mofussil Buses (Operation between District Capitals) and Express Services (Operation Between more than 250 Kms),establishment cost will be considerable reduced in appointing full time conductors for the buses.

-

As with many aspects of work and employment in the transport sector, this is a ‘gender intensified’ barrier that would benefit men but especially women if more adequately addressed by the social partners and the state. The burden on women of combining productive and reproductive responsibilities inevitably affects their ability to retain employment and has an impact on relationships within the household (e.g. calculations to determine whether men or women will realise a greater financial return on investments in human capital). Any society or sector that desires to improve the employment prospects of women must address all dimensions of work life and not disadvantage women because of their multiple productive and reproductive roles.

-

If working conditions are attractive, and there are opportunities for training and development, then women are more likely to build a career in the transport sector. To do this requires on-going training and development, which companies are often reluctant to offer to women because of anticipated interruptions to their career.. For too many women in the transport sector, jobs do not develop into careers – they remain stuck in lower paid, lower level positions, denied the opportunities for progression available to men and therefore more likely to quit or have little or no desire to return to the sector after a period of interruption.

Precise Takeaway

With the achievement of women participation in transport, it is clear that the provision of public transport policies and services which meet the needs of women will not only satisfy the needs and aspirations of the majority of public transport users - i.e. women, they will also tend to make its use more attractive to men and children as well. What has all too obviously not worked is the converse: it has been seen repeatedly that building public transport systems around the needs of men has not tended to produce a system which adequately meets the needs of women.